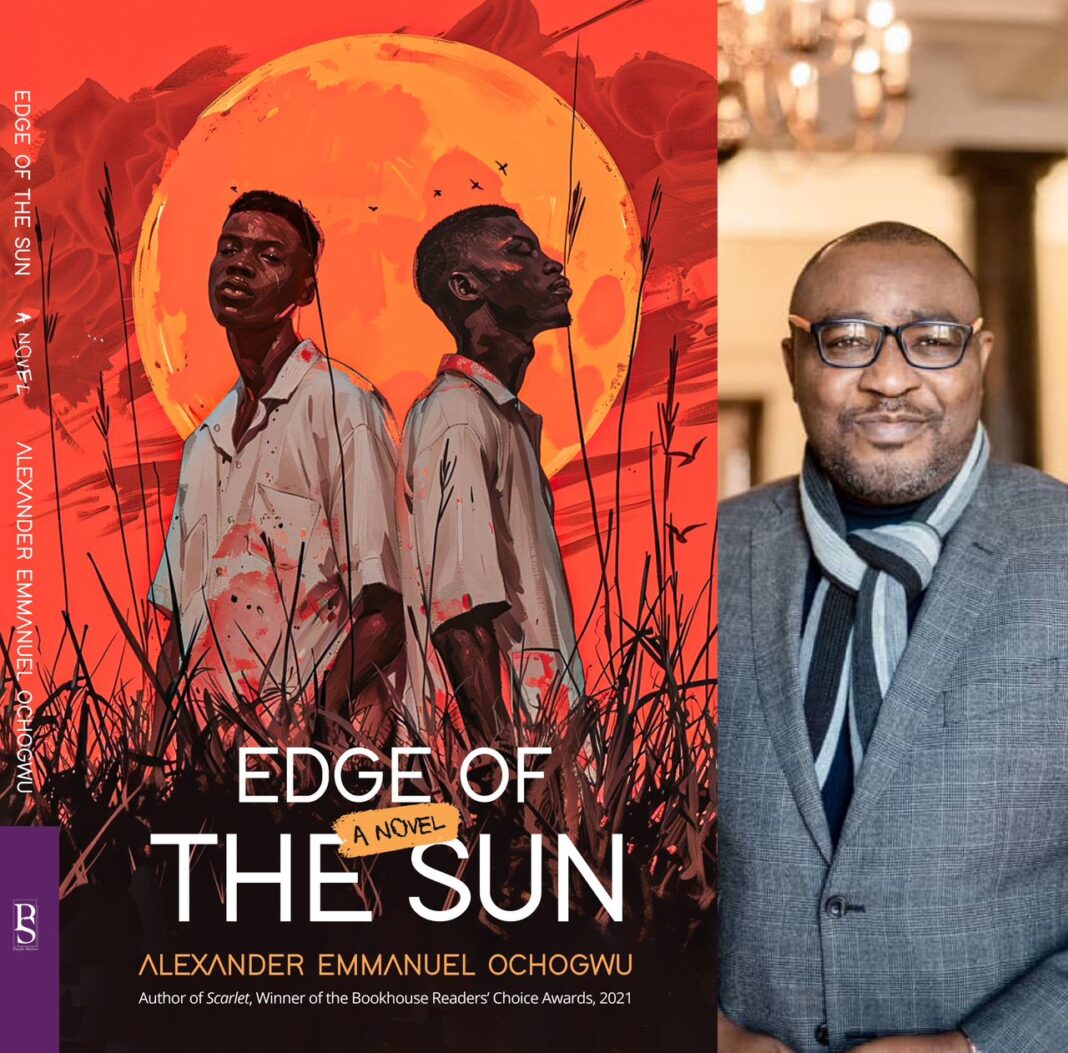

“Intervention Strategies for the Boy Child in the Twenty-First Century”

A Review of Dr. Alexander Emmanuel’s Edge of the Sun

By Professor Chris Kwaja

In a nation where conversations on insecurity are often dominated by guns,

numbers and political declarations, Dr. Alexander Emmanuel’s Edge of the Sun

reminds us that beneath every insurgency lies a bruised childhood. His novel is

not just fiction, but a quiet revolution that turns the mirror of violence toward

our collective conscience. It compels us to ask how Nigeria’s boys such as Sim,

Jaja, Little Abdul and countless others like them, become the raw material for

conflict.

As someone who has worked across policy, research and field operations in

peace and security, I recognize Edge of the Sun as more than a story— it is a

strategic reflection. It captures, through narrative, what policy documents often

fail to translate into empathy: that insecurity in Nigeria is sustained not only

by weapons but by wounds. Emmanuel’s decision to approach national

security through fiction is both bold and timely. It expands the scope of softpower engagement by positioning literature as a tool of social intelligence,

deradicalization and identity reconstruction.

The Novel as Security Mirror

At the heart of Edge of the Sun is the journey of two boys—Sim and Jaja—

whose lives are shaped by a nation in moral disarray. Through their eyes, we

see a generation raised amid broken families, political greed and the corrosion

of community values. The story moves between Lagos, Bodo and Gidan Rana,

revealing the layered geography of violence in Nigeria: urban corruption, rural

decay and militant extremism. Each setting functions like a security case study,

demonstrating how unaddressed local conflicts evolve into national crises.

In Bodo, cult violence erupts between the Bowe Boys and Aye Boys, mirroring

the real dynamics of gang networks that grow around environmental

degradation and oil theft in the Niger Delta. Emmanuel’s decision to locate the

story in this context is deliberate: it links economic marginalization with the

moral injury of youth. Sim’s forced relocation from Lagos to Bodo after his

mother’s abduction becomes a descent from comfort into chaos and,

symbolically, from innocence into radicalization.

What follows is not simply a coming-of-age story but a sociology of recruitment.

Sim and Jaja, drawn into cult life, experience the false brotherhood and

adrenaline that extremist groups offer in real life, which are belonging, identity

and revenge. Their transformation illustrates a crucial truth of conflict studies:

no one is born violent; violence is socialized. The novel’s genius lies in its ability

to dramatize this process with human empathy rather than condemnation.

From Radicalization to Redemption

Emmanuel’s fiction takes a decisive turn when Sim and Jaja encounter

Professor Uzoba, an academic who rescues them through education and

therapy. Uzoba’s work resembles what peace practitioners call a communitybased deradicalization model: identifying at-risk youth, isolating them from

violent influences and providing cognitive and moral rehabilitation. His

intervention mirrors the real-world gaps in Nigeria’s counter-extremism

strategy.

The Professor’s philosophy is straightforward—violence can be unlearned

through knowledge, dialogue and purpose. By sending Sim and Jaja to

university, Uzoba restores their agency. Later, when they establish Phantom

City, a rehabilitation centre offering counselling, medical care and skills

training to former cultists and abused children like Little Abdul, the narrative

completes its cycle of transformation.

From a policy perspective, Phantom City is not just a fictional institution; it is a

prototype for what our deradicalization system could become if humanized. It

shows that effective intervention must blend psychological healing with

education and reintegration. It also recognizes that community-driven

solutions often succeed where bureaucratic programmes stall.

Lessons for Nigeria’s Deradicalization Framework

Nigeria’s Operation Safe Corridor (OSC) represents one of Africa’s most

ambitious attempts at rehabilitating ex-combatants. Yet, as various

assessments have shown, OSC struggles with weak community buy-in, limited

post-training opportunities and recurring stigma. In many cases, the

deradicalized are warehoused rather than reintegrated. Edge of the Sun

exposes these structural flaws, not through policy critique, but through the

lived experience of its characters.

Sim’s early indoctrination and later recovery illuminate the stages often

missing in government programmes: early-stage prevention and sustained

post-rehabilitation engagement. His story reinforces the need for continuumbased deradicalization, where prevention, transformation and reintegration are

treated as interlinked rather than sequential phases.

Equally important is the novel’s psychological insight. Little Abdul’s abuse by

his guardian represents the unseen traumas that feed cycles of violence.

Nigeria’s counter-extremism frameworks rarely prioritize mental health, yet

Emmanuel’s narrative insists that psychological recovery is the real front line.

Without addressing trauma, we are merely disarming individuals while leaving

their minds weaponized.

The Boy Child as Security Actor

Where the novel speaks most powerfully to national strategy is in its portrayal

of the boy child. Emmanuel’s young male characters—Sim, Jaja, Little Abdul

and Priye—are not just victims of conflict; they are mirrors of a neglected

demographic. Contemporary security data show that boys aged 10–18 in

conflict zones face the highest risk of recruitment, sexual abuse and

displacement. Yet, Nigeria’s child-protection and peacebuilding policies rarely

distinguish their specific vulnerabilities.

Edge of the Sun demands that we re-examine the boy child as a strategic

population group. It proposes that early mentorship, education and cultural

engagement are the most effective counter-insurgency investments a state can

make. The rehabilitation of Sim and Jaja, guided by Uzoba and later Ebiye,

becomes an allegory for what inclusive national security could look like: one

that treats knowledge as defence and empathy as deterrent.

Culture as Counter-Narrative

One of the novel’s lasting metaphors is its title. “Edge of the Sun,” adapted

from the Hausa phrase Inna karshin rana, symbolizes standing on the

boundary between darkness and illumination. For Nigeria, this metaphor is

national. We are perpetually at the edge—between fragility and resilience,

despair and possibility. Emmanuel’s writing suggests that the choice to step

into light begins with culture.

With increasing exploitation of digital propaganda by extremist groups to

radicalize youth, literature becomes a counter-narrative weapon. Edge of the

Sun proves that fiction can compete with ideology by offering meaning, hope

and reflection. It calls on the state to invest in creative education, arts therapy

and storytelling platforms in conflict-affected communities. These are not

luxuries; they are long-term security measures.

Bridging Literature and Policy

Reading Edge of the Sun, I was reminded that national security is not achieved

through force alone but through the creation of humane alternatives.

Emmanuel’s background as a military officer gives his storytelling unusual

credibility. He writes not from imagination alone, but from observation—

showing how every conflict is both external and psychological.

In academic terms, the novel articulates what I often describe as “the moral

economy of peace.” This refers to the collective belief systems and social norms

that either sustain or undermine stability. By portraying the redemption of

violent youth through compassion and education, Emmanuel maps the

contours of that moral economy. His fiction thus becomes a contribution to

Nigeria’s non-kinetic security doctrine.

The novel’s realism also cautions against complacency. While Uzoba and Ebiye

represent idealistic interventions, their successes depend on local ownership.

For real-world policymakers, this means designing deradicalization initiatives

that are not externally imposed but co-created with communities. It also

underscores the need for legislative frameworks to secure funding, ensure

transparency and protect both beneficiaries and facilitators.

Toward a New Security Imagination

If there is one overarching insight from Edge of the Sun, it is that every society

must decide what to do with its damaged youth. We can either recycle them

into prisons and militias or re-imagine them as citizens of peace. The

establishment of Phantom City in the novel is emblematic of the second

choice—it symbolizes a nation’s willingness to heal itself.

In today’s Nigeria, where violence is decentralized and state authority often

fragmented, Emmanuel’s vision is profoundly relevant. It tells us that

preventing the next wave of extremism requires investment not in weapons but

in wellness; not in punishment but in purpose.

To operationalize this vision, I propose three priorities drawn from both policy

experience and the moral architecture of Emmanuel’s fiction:

- Develop a National Framework for Boy-Child Resilience—a cross-sectoral

policy linking education, mental health and peacebuilding at the community

level. - Institutionalize Literary and Arts-based Counter-Narratives within national

deradicalization programmes. Creative writing and storytelling should become

tools of civic re-education. - Reform Reintegration Systems to include psychosocial support, mentorship

and community sensitization—ensuring that returnees are accepted, not

alienated.

In conclusion, Edge of the Sun is both an artistic triumph and a policy

challenge. It reminds us that the future of Nigeria’s security lies not in the

accumulation of arms but in the cultivation of empathy. Through his

storytelling, Dr. Alexander Emmanuel transforms literature into a form of

strategic influence—one capable of doing what conventional policy cannot:

healing the unseen wounds of a nation.

Professor Chris Kwaja is a Professor of International Relations and Strategic

Studies, Country Director, United States Institute of Peace (Nigeria) and the

Special Envoy on Security to the Executive Governor of Plateau State